Home » Posts tagged 'india'

Tag Archives: india

Xi’s Napoleon Moment – Reposting Sandomina’s blog

For anyone interested in Asian Geopolitics, I can highly recommend “Insightful Geopolitics” by a writer whose pen-name is Sandomina. The posts are well-researched and, well, insightful. I sometimes don’t know the sources of the statistics quoted in the blog, but my gut feeling is that they are all from reliable sources.

Many people in the West are concerned about China’s growing economic might and how dependent their own industries are on Chinese supply chains. In Asia, Sandomina remarks, China has 14 neighbours with a common land border and 7 maritime neighbours. China has territorial disputes with all of them.

People everywhere would be well advised to take note of China’s rise. Depending on the way it’s internal politics develops, it can become a powerful engine for development and international growth. At present, all signs point to a belligerent China that reflects Xi Jingping’s personal thin-skinned sensibilities rather than statesmanship with a global perspective.

Having said this much, go to the link below and read about more about Xi’s Napoleon Moment here

Rethinking the World Order

According to economic historian Angus Maddison, in the year 1820, the Chinese economy was the world’s largest, accounting for approximately 33% of global GDP. At the same time, India’s was half that, with 16%, and a youthful United States around 1.8%. Europe ranked second in this GDP league table with 26.6%. (Here’s a link to the 200-page OECD report. If you’re interested, see p.46)

It was around this time that British opium traders began to export Indian-grown opium to China, an act, ostensibly in support of the principles of global free trade, that impoverished both India and China. The import of opium was illegal under Chinese law, but the fading Qing dynasty was unable to stop the smuggling, principally through Canton, or Guangdong as it is known today. In this period began what the Chinese now call “the century of humiliation” where they could not compete with superior western naval power and suffered internal fragmentation. In subsequent decades, China ceded territories to Germany, to Britain, to France and to Japan. One of the few happy results of these forced occupations is that China’s best beer, Tsingtao, comes from the Jiaozhou Bay area that was ceded to Germany. Tsingtao beer was listed as the world’s top-selling beer in 2017.

By 1952, the picture had changed dramatically. Europe’s share of world GDP was 29.3%, the US 27.5%. China’s GDP had dropped to 5.2% and India’s to 4%. Today, nearly 200 years after the first opium war, it looks as though China is resuming its old dominance, with close to 20% of world GDP; this time as a united country that willingly trades with other countries around the world. So, contrary to what is often written in the media, maybe China’s expanding global influence is not really so threatening. From the Chinese perspective, they are merely returning to their rightful place in the international world order. Rightful place this may be, but the accompanying geopolitical shifts are worrisome to many countries, especially Asian ones. India now wears a necklace of potentially hostile naval bases in Bangladesh, in Sri Lanka, and in Pakistan, all built and financed by China. Until Duterte came to power, the Philippine leadership worried about Chinese occupation of the Spratly islands that are claimed by six countries: Vietnam, Taiwan, Malaysia, Philippines, Brunei. China has now pre-empted the discussion by building a military base there.

The increasingly authoritarian rule of supreme leader Xi Jinping does not bode well for China. Neither does the crackdown on Uighur ethnic minorities in Xinjiang, or independence movements in Taiwan and Tibet. Meanwhile, climate change looms over the entire world, so amidst rising prosperity in the region, there are tough geopolitical questions to be dealt with in every corner of it. So here’s a toast to some schoolgirl or boy who, unknown to the world today, will come to power and find answers to some of these questions in the decades ahead.

Life After IIASA 1975-2013: Five Years On

February 2018 will mark five years after my retirement from IIASA. These five years have been full of new experiences, travel and writing. My wife and I have also attempted during this time to modify our lifestyle to be as carbon neutral as possible. Measures include living without a car, using a bicycle for shopping and public transport for travel where possible. Trips by air are unavoidable in the lifestyle we’ve chosen, and we’ve attempted to offset this carbon by buying solar panels for a farm school in India and a solar farm in Austria, 8 KW in all. These panels will apparently offset around 8 tons annually, but there’s still more to be done.

I first heard about sea level rise in a talk by paleo-climatologist Herbert Flohn at IIASA sometime in the late 1970s. At that time, many of the information requests that the IIASA library received were about global effects of a nuclear winter in the aftermath of nuclear war. Research themes changed quickly; interest moving to carbon dioxide emissions from fossils fuels, global warming, acid rain and stratospheric ozone.

In the intervening years, the reality of human-induced global warming has been accepted by all but the most ideologically blinkered societies worldwide. Travelling through parts of rural India soon after retirement in 2013, I saw repeated instances of people taking actions to adapt to climate change; water harvesting to compensate for unprecedented droughts, reforestation efforts; introduction of organic farming methods and drought resistant crops. I’d like to think that much of the credit for these adaptation and mitigation actions goes to studies by IIASA and other research institutions worldwide; scientific studies whose results filtered down over decades through the media and drew attention to these problems early on. There’s no way to prove this, and some of the water harvesting systems I saw were really ancient structures brought back into use. See more about that here

Efforts in 2015 and 2016 to help establish a rural education and vocation center failed for a very positive reason. The five acres of land (2 hectares) that had been donated to us for school use by a well-wisher is worth approximately € 300,000 (€65,000 per acre at today’s prices). The donated property was fertile agricultural land and classified as such. The local administrative authorities refused permission to reclassify the plot for use as a school and insisted that the land remain in use for agriculture. This was a positive outcome, because one of our reasons for this choice of location of a school was to prevent displacement of the rural population by expensive housing projects that would only benefit urbanites.

However the effort was not wasted. Since then our local partners have decided to build an organic farm on the land and use the experience gained to encourage the farming practices of communities in neighbouring villages. One function of this farm would be to develop markets for organic produce. We discovered several small companies in the area that offer free midday meals to their workers. They were happy to find a local supply of good vegetables. One enterprising factory owner offered his workers three free meals a day, sourcing all the vegetables from his own backyard. The vegetables he showed us were grown in plastic tubs lined with mats made of nutrient-rich hemp fibers. In fact, the method is so successful that he gives away growing kits free to any of his workers who want one for their own families’ use.

An encounter in early 2017 with a conservationist who runs a hatchery for Olive Ridley turtles on the sea coast near Chennai city led me to Tiruvannamalai, a town 200 km to the south-west. Here is an organic farm school where text-book sustainable living is practiced in the most lively and joyous manner possible. There are around 100 children in the school, ranging in age from 8 to 18. The links below will give an idea of activities at the school.

http://www.marudamfarmschool.org/

https://yourstory.com/2017/12/2-lakh-trees-ngo-regenerating-forest-tamil-nadu/

http://www.theforestway.org/greening/planting.html

In addition to organic farming, environmental conservation and education, the school also works with villagers in the surrounding countryside, reforesting the hill that dominates the temple town, planting around 15,000 trees a year. The school’s efforts inspired us (myself and a few friends in India) to help them become energy self-sufficient, adding 5 KW of solar panels to the three they already had. Together with battery backup, the school is now completely independent of the grid. (photo attached).

This activity led me to a thought. If IIASA’s work ultimately inspired these kinds of sustainability acts, what about IIASA’s own carbon footprint? IIASA’s alumni are scattered all over the world. What if we joined together, wherever we are, and worked to offset IIASA’s carbon emissions? Such actions would benefit our own communities, wherever we may happen to live. To kick-start this effort, I’ve decided to fund the planting of 1000 trees in 2018 through the farm school mentioned above. If each tree sequesters 25 kilos of carbon (as a rule of thumb, regardless of species), this would offset 25 tons of the Institute’s annual carbon emissions.

Should this be a formal organized effort? Readers’ suggestion welcomed here. All we would need is a virtual platform where one can document one’s own efforts and have a running tally. Ultimately the goal is to achieve carbon neutrality, not only for the Institute, but also for the communities in which each one of us lives. But, as for so many initiatives, IIASA could be a starting point.

On a personal note, the years since retirement have been very fulfilling. Thanks to my wife’s job, we were able to spend 2 idyllic years on an island paradise near Hong Kong. This provided background material for a work of fiction, Grace in the South China Sea. There are two sequels in the pipeline (The Trees of Ta Prohm, and Heartwood), to appear in 2018. Look for the earlier books and announcements on the Amazon author page here.

See this author’s page at Amazon.com to read more of his work.

Poramboke – Singing the Tragedy of the Commons

The “Tragedy of the Commons” is a term applied to the problem of shared resources in societies. All over the world, resources that are shared by all its members (the commons, e.g. public grazing lands, ponds, lakes) are in danger of over-exploitation and long-term degradation. This is what is happening to the world’s air, the oceans, the world’s fresh water, and all the other public resources that we used to take for granted as a basic human right. The world’s common resources are under siege from mighty forces; industrial, economic, demographic. It does not seem right, it is not right, for us to say that all citizens of the world (and those as yet unborn) should not enjoy the same freedoms that we do. And yet we continue to consume more, in the name of increased prosperity and well-being. The Tamil word for commonly owned public land or wastelands is “poramboke.”

How much is enough? Short question. No easy answers. I have met many interesting people recently, who are searching and finding answers, each in their unique way. The video attached above is of south Indian Carnatic singer TM Krishna, along with other eminent musicians, singing the tragedy of the commons in a song with powerful, compelling lyrics.

Poromboke ennaku illai, poromboke unnaku illai, Poromboke ooruike, poromboke bhoomikku he sings

Poromboke is not for me, it is not for you. Poromboke is for the city, it is for the Earth.

These past 3 months, as I travelled in different parts of the Tamil country, I see a powerful re-awakening of traditional values, and I will try to document some of my observations in the coming weeks.

Touched by the Invisible Hand

I bought a motorcycle for extensive local travel in an Indian city. A few friends and most of my middle class extended family were aghast when they heard. This is a form of suicide, they said. Look at the state of traffic on the roads. You need to protect yourself in a car.

Here are my answers to the criticism. First, there’s enough pollution already, and I’d rather travel at 55 km/liter with a 100cc motorbike rather than around 20km/l with a small car. Of course, the best alternative would be an electric vehicle powered by renewable energy, or else public transport, but neither of these options is currently practicable for my purposes.

Second, as the image above shows, progress is much faster with two wheels on congested roads. And third? I was reminded of the third reason this week when I had the painful news of a dear friend killed in a freak traffic accident in a European city, one of the safest cities in the world. I grieve at the loss. My take from the deep sadness I feel is this: seize the day, live as carefully and as well as you can, but follow your heart and do as you think you should do.

From Wellesley to Wellington: Auction Sale for Nostalgia Buffs

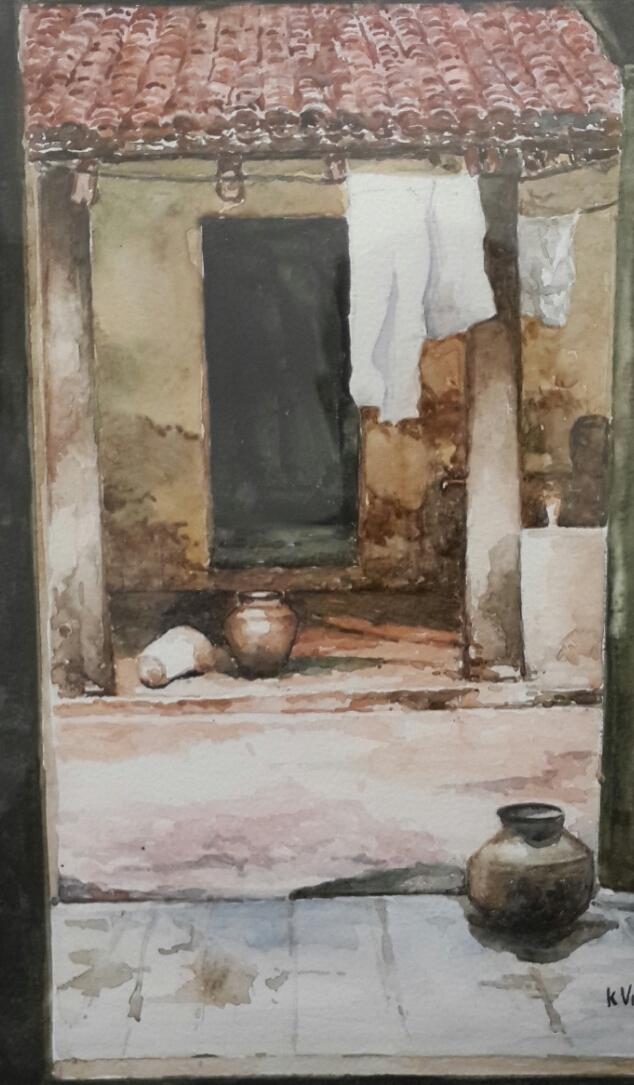

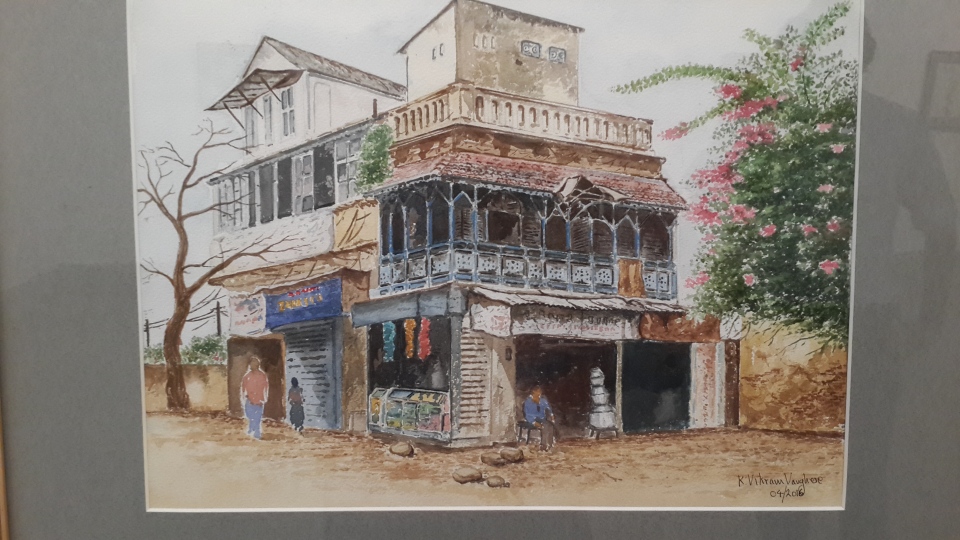

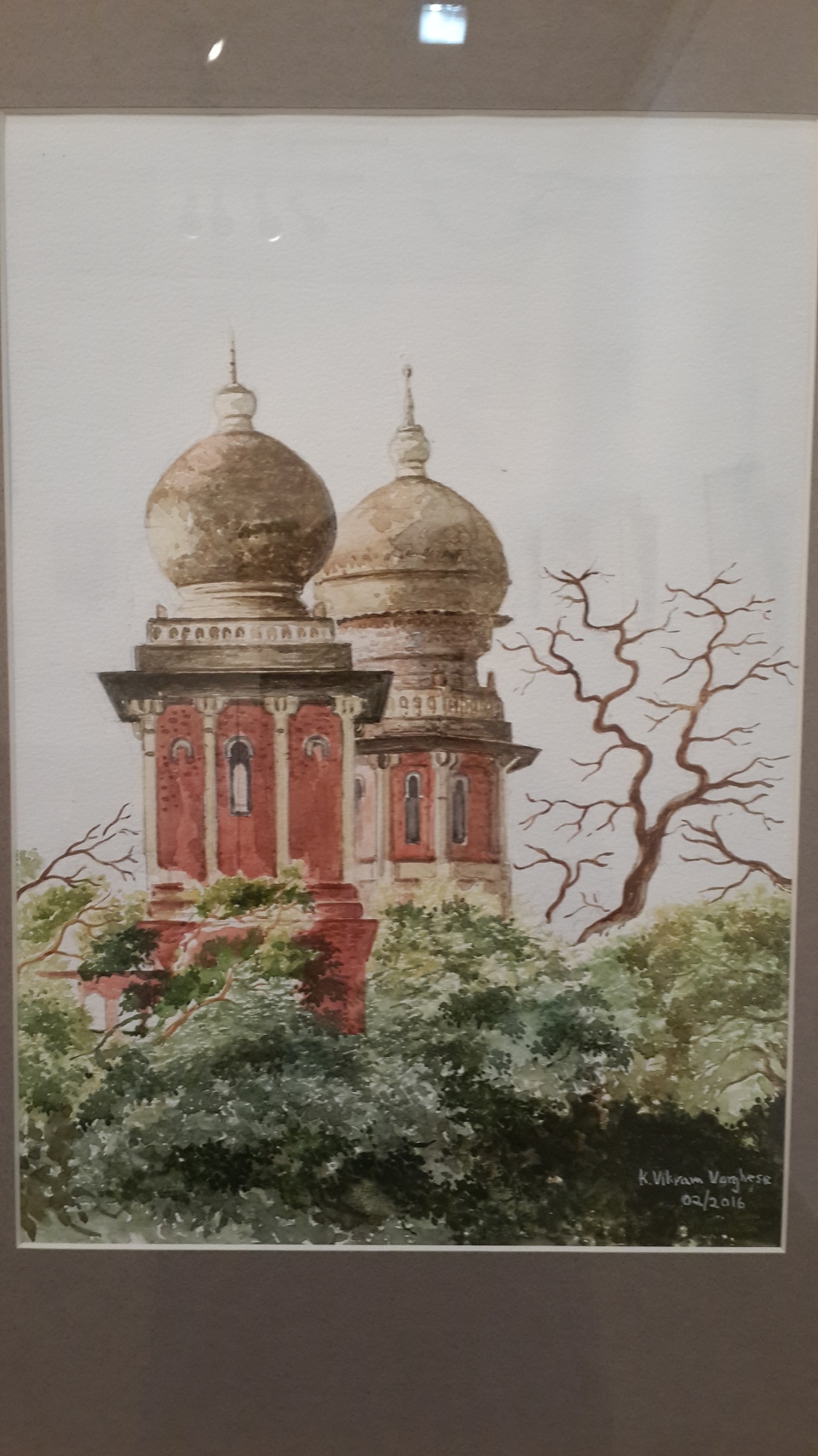

I recently attended a Vernissage of watercolor paintings by Chennai based artist Vikram Verghese. Several of his paintings caught my fancy and I bought the one pictured below, mainly as a gesture of solidarity with a talented young artist. I also had another thought at the back of my mind. A friend had remarked at the exhibition: “Why don’t you auction it afterwards to raise money for the rural education center you’re helping to build?” It appeared to be a splendid suggestion and that’s just what I’m doing here.

Ruins of Wellesley House, Fort St. George, Chennai, India, home of the future Duke of Wellington, 1798-1800. Watercolor by Vikram Varghese

The painting below is on sale to the highest bidder. Floor price €1000 (or US$ 1060/Rs. 72,000). This should be sufficient to buy almost 2 kW worth of solar panels and battery storage at today’s prices. The excerpt below is from an article by local historian S. Muthiah, who explains why the ruined building shown in the painting is historically significant. It appeared in the online edition of “The Hindu” newspaper on the 13th February 2017.

FEBRUARY 13, 2017 00:00 IST

My favourite bed-time reading the past couple of years has been the Richard Sharpe series by Bernard Cornwell, in which he puts his hero in the middle of battles from Seringapatam in 1799 to Waterloo in 1815, Cornwell has Sharpe the foundling rise from private to officer through 16 campaigns the British fought. They’re a fun read at one level, but to me the books are much more. They are brilliant, well-researched descriptions of battles and wars with often a bit more than a nod to the political history of the times.

Throughout the series there is a Sharpe-Arthur Wellesley relationship which began in Madras. In my latest read, the connection cropped up again. Coincidentally there arrived an invitation for a water-colour exhibition,Disappearing Dwellings by K. Vikram Varghese, and on its back cover was a picture of a dilapidated house, a house almost collapsing. That house was where Wellesley had lived from his arrival in Madras in 1798 as the Colonel of the 33rd Regiment (after having bought his commission) till he marched to Seringapatam in 1799 during the Fourth Mysore War.

This building, Wellesley House , was built in 1796 and is one of the 16 Archaeological Survey of India-protected monuments among the 30 or so buildings in Fort St. George.

The portion of the house seen in a state of collapse met that fate during the 1980 rains.

Since then, though the main portion still stands tall, talk of restoring the buildings gets nowhere due to territorial rivalries.

With talk of the Army moving out of the Fort, very likely sometime this year, perhaps the ASI will get around to restoring this historical building as well as its protected neighbours and then make a bid for World Heritage Site status for Fort St. George.

Why ‘historical’? Arthur Wellesley took his first steps to serious soldiering while living in this house and went on from here to eventually become the Duke of Wellington, a military legend who had while in India sworn by the Madras Regiment.

Anyone interested in bidding can make an offer on the E-Bay listing at this link. This auction ends in a week, on the 5th of March, 2017.

Monsoon Wedding

The wedding was in Kerala, a state in India whose advertising blurb labels it “God’s Own Country.” Argentinians and Brazilians also make rival claims to have been similarly favoured by the Creator, while each runs the others’ country down “Yeah, God gave your country everything, but then he created you people to compensate!” In the case of Kerala, the affable people of neighbouring Tamil Nadu harbor no such pretensions, laughingly noting that several million people from Kerala prefer to live with them rather than in their own home state. The wedding eve reception and reception were at holiday resorts at Kumarakom.

Kumarakom is situated on the banks of Vembanad lake, apparently the longest lake in India, whose wetland system covers an area of two thousand square kilometers. Much of Kerala’s claim to God’s bounty comes from the backwaters, large estuarine stretches of brackish water that gives rise to a very rich ecosystem. Part of the lake holds the fresh water that drains into it from several rivers, and this fresh water section is separated from the brackish portion by mudflats. The lake is at the heart of ‘backwater tourism’ in the state, with hundreds of “kettuvallams,” floating homes on motorized traditional boats. The riverboat network spans 200 km from north to south and the lake teems with giant prawns and several other types of freshwater fish.

Meanwhile, the bride and groom were happily united at a church in neighboring Kottayam town. It was a glorious wedding with guests travelling from around the world to attend. The groom wore a kilt, befitting his antecedents, and the bride wore a matching tartan sari, designed by the groom’s mother. All in all, a fitting Kerala wedding for the 21st century. The wedding photos belong in a family album rather than this blog, so none appear here. But if you ever are invited to a wedding in Kerala, my advice to you is, go!

For more by this author, see his Amazon page here or on Google Play

Dam(n)ed Words

“In the beginning was the word,” the book of St. John begins, in the King James version. “And the word was with God and the word was God.”

In the Katha Upanishad (approximately 5th century BCE), OM is related to the first primeval sound and the creation of the Universe, in an eerie echo of modern physics and the sounds that presumably accompanied the Big Bang. However, this analogy cannot be drawn too far, since the word OM has multiple meanings and interpretations in the Upanishads and in Buddhist belief. The Huffington Post says “Om is also considered the mother of the bija, or “seed” mantras — short, potent sounds that correlate to each chakra and fuel longer chants (like, say, Om Namah Shivaya). Depending on who you talk to, it relates to either the third eye or the crown chakra, connecting us to the Divine. No wonder it is core to some Buddhist systems and other Indian religions. Some say it’s even among the sounds recorded in deep space — on NASA’s website, Earth itself sounds a bit om-y.”

Coming to the present day, which is our primary concern here, Lucia Graves writes in the Guardian (July 13th, 2016) “It used to be that you had to read between the lines to determine that Donald Trump was stoking racial resentments. And it used to be that the subjects of his racial animus were mostly immigrants. But now, increasingly, he’s casting a wider net and amping up his rhetoric.” Also in the Guardian of the same date, another headline says, “Labour’s Luciana Burger receives death threats telling her to ‘watch her back.'” Because she’s Jewish. Chilling news, seven decades after the horrors of the Shoah!

In Bangladesh, India and Pakistan, the language of intolerance has grown more strident in recent years, often drowning the voice of reason. The Islam of the Sufis seems to be disappearing from public discourse, and the all-embracing tolerance of Hinduism seems to be hardening at its edges. In the Middle East, the intolerant rhetoric of various groups has led to spectacular and bloody breakdown of civil society in the region.

The world as we know it began with words. Even so, the unraveling of our world and civilization as we know it, also begins with words. It begins with the language of the bigot, the language of the nationalist, the language of the religious fanatic speaking on behalf of God (presumption or megalomania?), the language of the intolerant, the language of politicians looking to increase their grip on power. In politics today, the language of intolerance seems to be gaining ground, becoming socially acceptable. Socially acceptable? That means us. That we accept it. Unless we emphatically refute it at every encounter. By casting votes, by speaking up, by voting with our feet. The last case scenario is, sadly, what prompts the widespread immigration we see today.

See more work by this author on his Amazon page here or on the Google Play store.

Saving the Tiger

Ranthambore National Forest and Tiger Reserve is a stunningly beautiful place that spreads over 450 sq. km. Writers like Jim Corbett and Rudyard Kipling have painted vivid portraits of Indian jungles for readers in the English speaking world. On a recent visit to Ranthambore, sitting in an open jeep, slowly winding its way along rutted jungle trails, tales of Mowgli, Bagheera and Balu the bear seemed to come alive. She expected to see a barefoot boy in a loin cloth peering out from among the tall grasses. Instead, she came face to face with …Shere Khan.

The moment was so unexpected, so pure, so anti-climactic that there seemed to be magic in the air. Noor is also known to the park rangers as Mala, a name that means ‘necklace‘ for the decorative, beadlike stripes on her flank. She had apparently just fed at dawn, the remains of the kill lay somewhere in the grasses nearby, her belly was full, and she was tired and too sleepy to investigate the little open jeep with three occupants parked at a respectful distance.

These magnificent animals are under threat from us humans. Ironically, one way to save them might be to bring more humans to visit them in their natural surroundings, just like the passenger in the jeep who watched her in awed silence for nearly two hours. For every tourist who comes to see them here, there are perhaps two or three locals who earn a livelihood, people who have been displaced from their own natural habitat in the jungle, displaced by the need to preserve wildlife. The villagers who used to live in Ranthambore forest were relocated when the tiger reserve was set up. These displaced people had to carve out a new existence in small settlements surrounding the jungle that was once their home.

We met one of the displaced people, a Rajput by the name of Dharamveer. He was proud of his forbears who had built forts and castles in these hills and jungles, and today he was one of the lucky ones; someone who had done well by doing good. When he was displaced from the forest, Dharamveer had trained as a tiger painter, painting iconic portraits of Shere Khan with the finest of strokes using delicate brushes that were a mere three or four hairs thick. This fine work gave the tigers in the paintings a lustrous lifelike glow that seemed to move as they caught the light. Buoyed by this success, he assisted widowed women to retrain in other handicrafts and has created a thriving business selling their work.

We visited his store after the safari and were welcomed by the artisans who proudly showed us their wares. There was exuberant patchwork art, as well as many other fabrics, woven on rural handlooms, carvings, tribal paintings and animal protraits. As usual, there was more than one person could buy, but an American friend is exploring the market for these attractive products outside India. More on that will follow in a later posting.

For more by this author, see his Amazon page here.