Home » history (Page 4)

Category Archives: history

Putting Methuselah in the Shade – World’s Oldest Trees

Ever since I first read Roald Dahl’s Charlie and the Great Glass Elevator as a bedtime story to my daughter nearly two decades ago, I’ve always thought of the Bristlecone Pine that grows somewhere in Nevada as the oldest tree in the world. In the story, Willy Wonka tells the boy Charlie that the oldest living thing in the world is this pine tree. Willy Wonka says the tree is more than 4,000 years old, but Wikipedia shows a photograph of a suitably gnarled tree and states it is actually 5,065 years old.

Of course there are other contenders like the magnificent Hundred Horse chestnut (Castagno dei Cento Cavalli) in Sicily, reputedly 2-4,000 years old, and other Bristlecone pines from the same forest. Apparently there is yet another that is claimed to be (an impossible-sounding) one million years old. This is the Pando, in Utah, a collective of aspen tree trunks, all genetically linked by a common root system that has apparently survived a million years.

To me, this sounds like cheating, even if the root system’s age is impressive by any standards. Not to be outdone, the magazine Nature published an article in 2003 that claims the gingko tree is a living fossil. Recent finds show that gingko species have remained unchanged for the past 51 million years and show remarkable similarity to species that lived during the Jurassic period, hobnobbing with dinosaurs, 170 million years ago.

For more by this author, see his Amazon page here.

Women and Wild Savages: Book Review

Synopsis: (from the Amazon website) At 18, Lina is an aspiring actress and the stunning daughter of Viennese coffeehouse owners. When the imperial capital’s most sought-after bachelor, Adolf Loos, unexpectedly proposes, she eagerly agrees. But the honeymoon is short-lived. Her “modern” husband might be friends with women activists but his publically progressive views do not extend to his young wife. Thank goodness for the sympathetic ear of Café Central’s beloved, old poet, Peter Altenberg. But when Adolf Loos unwittingly pushes Lina into the arms of his activist friend’s handsome son, Lina becomes entangled in a web of desire, jealousy and intrigue. No man’s love is unconditional. As the three friends rival to mold her into the perfect wife, muse and lover, Lina strives to recall the woman she once imagined herself to be. Fact and fiction weave together with history and romance in this tragic yet inspiring tale of Lina Loos’ struggle for love, liberation and self-fulfillment during her years of marriage to the renowned architect, Adolf Loos.

Set in the early 1900s in fin-de-siècle Vienna, Women and Wild Savages tells the timeless story of a person’s journey to recognize and be herself in a world determined to make her into someone else.

One of the first books I read about Austrian history nearly 4 decades ago was Frederic Morton’s hugely enjoyable “A Nervous Splendor.” This historical novel provided a vertical slice-of-life view of Viennese society in the closing decades of the Habsburg empire at the turn of the 19th century to the 20th. I then read many books about this fascinating period. William Johnston’s scholarly collection of essays, “The Austrian Mind” stands out, as well as Carl Schorske’s “Fin de Siècle Vienna.” Where Morton’s work gave a vertical view of life in the Vienna of the time, KC Blau’s novel gives a complementary, horizontal glimpse of Viennese society. Where Morton’s work was history written as fiction, this novel is more of a fiction written as history (although based on true events). Anyone who has enjoyed any one of the three above-mentioned books will surely give this novel a 5-star rating for its authentic recreation of the atmosphere and mores of the time. Readers who know nothing of Vienna will perhaps miss the authenticity of the period details but will surely enjoy the writing and the development of the characters. So while my personal opinion inclines to 5*, I’ve decided to rate it a 4* overall for the benefit of the average reader. I look forward to reading more of the “Vienna Muses” series as and when when they are published.

For more by this author, see his Amazon page here.

The Flea on the Behind of an Elephant

Scroll backwards in time to the early 1970s. US President Richard Nixon appointed the Atomic Energy Commission (AEC) to produce a study of recommendations on “The Nation’s Energy Future” based on advice from the National Science Foundation (NSF). Requesting the AEC for energy prognoses is akin to asking a tiger for dietary recommendations; there will surely be no vegetables on the menu! Dr. Dixy Lee Ray, chair of the AEC, predicted in her summation of the report that “solar would always remain like the flea on the behind of an elephant.” In the early 1980s I knew another eminent researcher, Dr. Thomas Henry Lee, a Vice President for research under Jack Welch at General Electric, who often stated that nuclear power would produce “energy that is too cheap to meter,” essentially free.

The AEC study, when it was published, proposed a $10 billion budget for research and development with half going to nuclear and fusion, while the rest would be spent on coal and oil. A mere $36 million was to be allocated to photovoltaics (PV). Dr. Barry Commoner, an early initiator of the environmental movement, was intrigued that the NSF had recommended such a paltry amount for solar. In the 1950s he had successfully lobbied for citizen access to the classified results of atmospheric nuclear tests and was able to prove that such tests led to radioactive buildup in humans. This led to the introduction of the nuclear test ban treaty of 1963.

Dr. Commoner’s own slogan (the first law of ecology is that everything is related to everything else) prompted him to question the AEC’s paltry allocation for solar PV, especially since he knew some of the members of the NSF panel who advised on the recommendations. He discovered the NSF panel’s findings were printed in a report called “Subpanel IX: Solar and other energy sources.” This report was nowhere to be found among the AEC’s documents until a single faded photocopy was unexpectedly discovered in the reading room of the AEC’s own library. The NSF’s experts had foreseen in 1971 a great future for solar electricity, predicting PV would supply more than 7% of the US electrical generation capacity by the year 2000 and the expenditure for realising the solar option would be 16 times less than the nuclear choice.

Clearly, the prediction of 7% solar electric generation has not yet happened, but current efficiency improvements in photovoltaics and battery storage technologies point the way to an energy future far beyond what the NSF predicted in 1971. Fifty years from now, it is nuclear power that is likely to be the flea on the behind of a solar elephant.

Molybdomancy

I started off intending to write about the Austrian New Year’s Eve custom of Bleigiessen and learnt several things today. First, the posh name for the practice is molybdomancy: the art of divining the future from the shapes of molten metal that is quickly thrown into cold water. Second, this is not only an Austrian custom, but is widely practiced in Germany and in the Nordic countries as well. Apparently in Finland, the practice goes by the name of uudenvuodentina and is quite popular. According to this source, the practice originated in ancient Greece and later travelled to the Nordic and Central European countries where the custom is still followed today, although the results are interpreted more in a spirit of fun rather than being taken seriously. No wonder the word molybdomancy has been quite forgotten!

Originally made from tin, nowadays bleigiessen sets are sold in the streets in the week preceding New Year in small bags consisting of half a dozen pieces of tin or lead alloy mixed with cheaper metal. The pieces are molded into shapes associated with good luck; horseshoes, pigs, chimneysweeps, toadstools or 4-leaf clovers. I bought a bag for New Year’s Eve and settled down with six of my nearest and dearest to see what 2015 has in store for us.

As you can see, the results are outstanding! 2015 is going to be a wonderful year for the family; two of them will perform exceptional deeds, while the rest will be merely brilliant. I wish all my readers a similarly uplifting prognosis.

The lake of deeds, and a dyslexic scholar

Ramcharitamanas (the lake of the deeds of Rama) is one of the greatest works of Hindu literature. Written by Goswami Tulsidas in the 17th century, it was written in Awadhi, a dialect of Hindi, and made the epic Ramayana, till then only read by the privileged few, (mostly upper castes) who knew Sanskrit, available to the common man. This widespread access to the Ramayana stories led to the birth of the tradition of Ramlila, the dramatic enactment of text, all over the north of India.

Tulsidas lived during the reign of Mughal Emperor Akbar (the great, 1556-1605) who was noted for his religious tolerance, emphasised by his promulgation of Din-i-Ilahi, a religion derived from a syncretic mix of Islam, Hinduism, Zoroastrianism and Christianity. To underline the point the Emperor took three principal wives from three religious faiths; Muslim, Hindu and Christian. Presumably due to Akbar’s religious tolerance, the enactment of Ramlila’s beloved text spread through Mughal lands and were adopted by the Phad singers and puppeteers of Rajasthan where they are still performed today (see my earlier post: Facebook for the Gods). Akbar was believed to be dyslexic, so he was read to every day, had a remarkable memory and loved to debate with scholars.

Written in seven kandas or cantos, Tulsidas equated his work with the seven steps leading into the holy waters of a Himalayan lake, Manasarovar. The lake lies on the Tibetan plateau and covers an area of 320 sq. km. The name comes from the Sanskrit words manas, mind, and sarovara, lake and refers to the belief that Lake Manasarovar was created in the mind of Lord Brahma before it was manifested on earth.

Akbar’s acceptance of different religious beliefs led Time magazine to note in 2011 “While the creed (i.e. :Din-i-Ilahi) no longer lingers, the ethos of pluralism and tolerance that defined Akbar’s age underlies the values of the modern republic of India.” Quite a tribute to a dyslexic scholar emperor who died four hundred years ago!

For more by this author, see his Amazon page or his link on Google Play

Wake up, world. China is changing.

The recent pro-democracy protests in Hong Kong have undoubtedly triggered change in China, according to Han Dongfang, a 1989 Tiananmen activist who now works in Hong Kong as a radio commentator. Since the gist of my post today comes from articles by other authors, a few acknowledgements are in order. First of all, thanks to Larry Willmore and his “Thought du Jour” blog posting on Hong Kong, reproduced in full (text in italics) below.

Secondly, thanks to Joe Studwell for his sensible and measured op-ed, published in the Financial Times of 7th October, on where the focus of the protests should lie (What Hong Kong needs is not a strategy that backs Xi Jinping, the Chinese president, into a corner, but one that resonates with his own mindset. This is why the protesters should refocus on Hong Kong’s tycoon economy, and the anti-competitive, anti-consumer arrangements that define it.) Anyone interested in Hong Kong should read the whole editorial!

And third, thanks to Han Dongfang and Quartz digital magazine for “advice from a 1989 activist.”

Joe Studwell is a freelance journalist based in Cambridge (UK). His latest book is How Asia Works: Success and Failure in the World’s Most Dynamic Region(Grove Press, 2013). He blogs at joestudwell.wordpress.com/.

Mr Studwell writes from the political left, so overlooks two features of Hong Kong that illustrate the paucity of free markets. First nearly half the population lives in public housing. Second, anyone with a Hong Kong ID is eligible for subsidized medical care in public facilities. There are 41 hospitals and 122 outpatient clinics run by the government’s Hospital Authority (HA), but only 13 private hospitals.

Echoes of a Million Mutinies: Hong Kong Day 5

VS Naipaul, in his prescient book, A Million Mutinies Now, published in 1990, painted a pointillist portrait of India, a country on the brink of an economic revolution. In it, he described the lives of scores of people from all walks of life; high and low, peasants and urban sophisticates, politicians and professionals. Based on these interviews, he showed a multi-hued society on the cusp of economic revolution. The economic revolution did come to pass in India, and is still taking place, with periodic stutters caused by many of the factors he mentions in his book; religion, caste, corruption, gender bias, or ethnic and linguistic divides.

Meanwhile China has raced ahead economically, leaving its equally populous Asian rival in the dust and smog of its success. Some political theorists surmise that democratic institutions are a natural outgrowth of economic prosperity. If so, China is ripe for the emergence of democratic institutions, nowhere more so than in Hong Kong, which has several decades of stellar growth rates and high living standards behind it. The generation of young people leading the sit-ins have grown up in a prosperous country with unrestricted freedom to travel. They have seen the world and now are impatient with the Chinese Communist Party’s attempt to dictate terms of the “One Country, Two Systems” policy promised by Deng Xiaoping in the early 1980s. Under this principle, there would be only one China, but distinct regions such as Hong Kong, Macau and Taiwan could continue with their own capitalistic and political systems while the rest of China used the socialist system. Walking through some of the barricaded streets of Hong Kong on October 2nd, day 5 of the “Occupy Central” movement (now also called the Umbrella Revolution because of the wall of unfurled umbrellas that were used to deflect the pepper spray that police initially used against the strikers), I was reminded by posters telling protesters to stay calm and avoid violence, that today was Gandhi’s birthday.

Two busloads of armed and uniformed policemen arrived in unmarked buses while we were passing by the police headquarters on Lockhart Road. At the nearby Legislative Council complex, the path was barred by a a solid phalanx of policemen behind barriers. A crowd of people stood opposite the barriers, and waited and watched, continuing their vigil. The atmosphere was very calm, with a few anxious faces in the crowd. A man walked around handing out surgical filter masks in anticipation of possible police action. Some young people sat cross-legged on tarpaulins, mats or flattened cartons, chatting in groups, reading or simply resting. A father squatted beside his son, visibly proud, arm around the boy’s shoulders, deep in conversation. A family sat together sharing a picnic. One girl was obviously immersed in her homework. Jason Ng, a Hong-Kong born lawyer, writer, pro-democracy activist and blogger, spent several hours after work helping students with their homework. Jason writes: There is a renewed sense of neighborhood in Hong Kong, something we haven’t seen since the city transformed from a cottage industry economy to a gleaming financial center…. This is the Hong Kong I grew up in. See his blog at http://www.asiseeithk.com/ for more of his posts and in-depth accounts.

It was a sultry afternoon. A young man and woman walked past us in opposite directions, spraying people with a welcome cooling mist of water from pump spray flasks. A knot of people stood in front of the Hong Kong Shanghai Bank Corporation, listening to a young man dressed in black T-shirt and trousers speak passionately in Cantonese. Most of the listeners were older, his parents’ generation, and they heard him speak with avid interest. One old man stood beside him eyes squeezed tightly shut to suppress tears, his mouth twisted in a grimace of pain.

We got home at 8 in the evening, moved by what we had seen, and wondering where all this would end. On the news, the Communist Party was making threatening noises, in typical fashion blaming foreigners for fomenting what is very clearly a home-grown protest. I searched for literature that documents societies moving from dictatorship to democracy and found this deeply insightful paper by former Harvard professor Gene Sharp. Here is the link.

http://www.iran.org/humanrights/FromDictatorship.pdf

The most important insight I gained from a quick reading of the above paper is Sharp’s idea of permission, where he explains that for a dictatorship to work, large segments of the population must give tacit permission for this to happen. What we are seeing in Hong Kong these days is the withdrawal of this permission to dictate. I wish for millions to support this courageous and peaceful protest in Hong Kong.

Jesus on a Lotus, Whispers in Nandi’s Ears

Christianity came to India before it came to most of Europe. It was probably (and plausibly) brought by Thomas the Apostle in 52 AD, the name being derived from the Aramaic Toma, meaning twin. St. Ephrem the Syrian writes in the 4th century that the Apostle was put to death in India and that his remains were brought to Edessa (fairly close to Antioch – Antakya – in modern-day Turkey) by a devout merchant by the name of Khabin. British historian Vincent A. Smith (1848 – 1920) says, “It must be admitted that a personal visit of the Apostle Thomas to South India was easily feasible in the traditional belief that he came by way of Socotra, where an ancient Christian settlement undoubtedly existed. I am now satisfied that the Christian church of South India is extremely ancient.”

According to tradition, Thomas landed on the Malabar coast, where his skill as a carpenter won him the favour of the local king. He was allowed to preach the Gospel and convert believers to Christianity. Thereafter, he moved across southern India for the next 20 years before he was finally killed near the coastal city of Madras, present-day Chennai, in AD 72 apparently because a local king grew jealous of his increasing popularity. Marco Polo, writing in the 13th century, states that the apostle was accidentally killed by a bird hunter who was shooting at peacocks in Mylapore. More recent interpretation of inscriptions found on the Pehlvi cross, near present-day St. Thomas Mount, by the Portuguese in 1547, suggest that the legend of Thomas’ martyrdom was based on mis-translations of the middle Persian script. Whatever the truth of the Apostle’s death, at this point in time, the legend of his martyrdom has been firmly established to a degree that makes it a fact, and there is a basilica built on the site of the tomb at San Thome, one of only three in the world directly associated with the 12 Apostles. (The other two are St. Peter’s in Rome, and Santiago de Compostela in Spain, dedicated to James). Since India is a land of syncretism, the tomb and St. Thomas Mount have been a pilgrimage site for Christians, Hindus and Muslims since at least the 16th century. The Indian church has adapted in India and adopted some of this syncretism by introducing certain Hindu rites (such as the tying of the thali at weddings). Knowing this, one is not surprised to find that the image of Christ on the cross at the cathedral of San Thome is flanked by two peacocks and that his feet rest on a lotus.

The area around the San Thome basilica belonged to the ancient city of Mylapore, or the city of peacocks. A temple was built in the 7th century AD in Mylapore. According to legend, Shakthi, the divine embodiment of the female, worshipped Siva in the form of a peacock, giving its Tamil name (Mylai) to the city. The temple was built to commemorate this, and is dedicated to Siva. Inside the temple is a statue of Nandi, the bull, which is Siva’s favourite mount, and also a gatekeeper to Siva and his consort Parvati. For this reason, it is believed that whispering one’s secret wishes in Nandi’s ear is as good as a direct request to Siva himself.

Being a good tourist, and wishing to hedge my bets in the afterlife, I prayed at the lotus feet of Jesus and whispered my innermost wishes in Nandi’s ear. Choose the link to follow this blog for updates on how well this strategy works in the coming months…

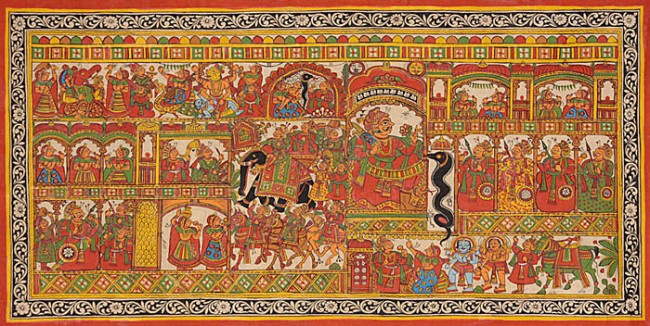

Facebook for the Gods: Phads and Puppets

William Dalrymple, in his fine book “Nine Lives” writes about the Phad singers of Rajasthan. As in traditional arts and crafts everywhere, the few remaining Phad singers and puppeteers are struggling to find audiences and sustain their livelihoods. There is a great danger that these rich traditions will soon be lost. Performances for tourist groups can help these artists survive, but to be really appreciated, the audiences need to be educated about the background to these stories (which are well-known to most traditional rural audiences) and this happens only with the most knowledgeable tourists, such as academics or researchers studying language and culture.

The Phad is a religious scroll painting of deities, a kind of a portable temple. As representations of the divine, these Phads, or painted scrolls, are treated with great reverence by the Bhopas (traditional singers) who carry them from village to village and fair to fair. The bhopas are bards, singers of epics, and perform prodigious feats of memory. The most popular epic is that of Pabuji. In the old days, when this 4000 line courtly poem was recited from beginning to end, something that rarely happens today, it took a full five nights of eight-hour performances to complete the narration. The art of the bhopa was handed down in families, from father to son. Sadly, the bards with their traditional accompanying musical instruments, called Ravannahatta, are disappearing from both town and country today.

Another dying art tradition is that of puppetry performances. Scholars believe that the tradition is thousands of years old. The puppets are called “kathputli” and fashioned from fabric, wood, wire and threads. In a desperate attempt to attract foreign tourists, puppeteers have “dumbed down” their elaborate plays based on the classic Indian epics, and developed contemporary five-minute local variations that neither do justice to the original, nor do they attract the tourists as they are meant to do. As Janis Joplin presciently sang in the 1960s, the sentiment behind Lord, can I have a Mercedes-Benz and the pursuit of material wealth has eclipsed the spiritual quest even in this land of 33 million gods.* There are several standard figures in the line-up of modern Rajasthani puppets. One of them is called Anarkali, who is modelled as a temptress and courtesan.

The second standard modern puppet figure is a Rajasthani version of Michael Jackson, who struts his stuff on the portable wooden stage and manages a passable moonwalk. The highlight of this 2-minute skit is when he raises his detachable head.

The third modern set piece is a snake charmer and his cobra, which begins to chase him around the stage after initially swaying to the charm of the flute in the background. Another character who often appears is a demure bride who suddenly is flipped over and becomes a male singer. Sometimes these puppets are handled with considerable skill, all the while accompanied by an ektara, a single stringed violin, and a shrill-voiced male singer who speaks through a bamboo reed.

*The figure of 33 million was pulled out of a hat after many discussions of the number of gods, where the count ranged from 3000 to 330 million, the last figure based on the reasoning that almost every third person in the country has his or her own personal deity. This seemed rather far fetched, but it is true that in every small village and town there are local version of the principal gods and lesser deities of the Hindu pantheon. If it all seems too foreign and confusing, look at it this way. There is but one god, Brahma, the creator of all things, and all the numerous deities are but one way of approaching him, just as Catholics pray to their favourite saint to intercede for them before the one God.