Home » Posts tagged 'energy futures' (Page 2)

Tag Archives: energy futures

Advice to a Billionaire

Michael Liebreich of Bloomberg New Energy Finance calls you one of three Black Swans in the world of energy and transportation this century; the other two being Fracking and Fukushima. You are often compared to Henry Ford, Thomas Edison, Nikola Tesla, the Iron Man, and shades of Einstein. You have advised Presidents. Heads of state visit your factories to see how they could improve the lives of their citizens. You stepped in without fanfare to donate money and provide power to a hospital in Puerto Rico after the devastation of Hurricane Maria. You issue audacious challenges to yourself and to others and sometimes miss deadlines, but ultimately deliver on your promises. Thousands, perhaps millions of people, speculate against you in the stock markets, hoping to make a quick profit from your failure. So far, they’ve been disappointed. But you put your money where your mouth is, so for every one of these speculative sharks, there are a thousand eager customers for your products and millions of well-wishers who hope you can help save the planet.

And yet you feel alone and unloved. You search for a soul mate and are willing to fly to the ends of the earth to find true love. You must know that love is like a butterfly. Be still and perhaps it will land on you. There are no guarantees, but the chances are infinitely greater if you cultivate stillness. And while you wait, exchange your loneliness for the wealth of solitude. As Hannah Arendt and Plato observed: Thinking, existentially speaking, is a solitary but not a lonely business.

As the father of five children, know also that their childhood is a precious and finite resource that you could use to your benefit and theirs. Childhood ends all too soon, so help them in whatever way you can to make good choices. You seem to have done so for yourself. In the meantime, millions of people around the world wish you well, as I do.

Carbon Countdown Clock

Ah, Trump. Has pulled the world’s second largest greenhouse gas emitter out of the Paris Accord. Was promised. Was to be expected. The one campaign promise that this prevaricating president did keep. The Guardian newspaper has usefully provided an online carbon countdown clock to show the world how time is running out. I believe Trump’s action might provoke the rest of the world to come together to save our common future.

https://interactive.guim.co.uk/embed/aus/2017/carbon-embed

Click on the link above to see how much time we have left.

Fossil Fuels are for Dinosaurs II

Wake up, Donald et al.! According to the Guardian of 6 January 2017,

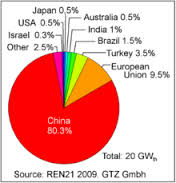

China now owned:

- Five of the world’s six largest solar-module manufacturing firms

- The largest wind-turbine manufacturer

- The world’s largest lithium ion manufacturer

- The world’s largest electricity utility

“At the moment China is leaving everyone behind and has a real first-mover and scale advantage, which will be exacerbated if countries such as the US, UK and Australia continue to apply the brakes to clean energy,” he said.

“The US is already slipping well behind China in the race to secure a larger share of the booming clean energy market. With the incoming administration talking up coal and gas, prospective domestic policy changes don’t bode well,” Buckley said.

For more by this author, see his Amazon page here, or links to his 4 books on the Google Play store.

The Decline of the Rest.

Oswald Spengler published the first volume of his two-volume life’s work, The Decline of the West, in 1918. Seventy-four years later, speaking at the Earth Summit, Rio de Janeiro in 1992, 41st US President George HW Bush, a decent man, declared, “The American way of life is not up for negotiation. Period.” This pre-emptive declaration by the leader of the world’s most powerful nation essentially castrated the noble intentions of the summit, to limit humankind’s exploitation of the earth’s resources to sustainable levels. The result of the Rio summit was Agenda 21, a non-binding, voluntarily implemented action plan for the 21st century. This was the paltry outcome of a nine-day meeting representing 172 countries attended by 116 heads of state, 2400 NGOs and 17,000 other representatives of indigenous peoples and ordinary ‘you and me’ types.

Oswald Spengler published the first volume of his two-volume life’s work, The Decline of the West, in 1918. Seventy-four years later, speaking at the Earth Summit, Rio de Janeiro in 1992, 41st US President George HW Bush, a decent man, declared, “The American way of life is not up for negotiation. Period.” This pre-emptive declaration by the leader of the world’s most powerful nation essentially castrated the noble intentions of the summit, to limit humankind’s exploitation of the earth’s resources to sustainable levels. The result of the Rio summit was Agenda 21, a non-binding, voluntarily implemented action plan for the 21st century. This was the paltry outcome of a nine-day meeting representing 172 countries attended by 116 heads of state, 2400 NGOs and 17,000 other representatives of indigenous peoples and ordinary ‘you and me’ types.

Twenty-one years after the US President’s declaration in Rio, the WWF designated the 20th of August 2013 as “Earth Overshoot Day;” the day that humanity has used as much renewable natural resources as the planet can regenerate in one year. In 2016, Earth Overshoot Day is estimated to have fallen on August 8th, after which date we’re drawing down the planet’s renewable resources for the rest of the year. Pity the poor planet! The American way of life is still not up for negotiation, and the rest of the world is rushing to catch up. If ever populous countries like China and India get there, the planet will be sucked dry and we’ll all have to follow Elon Musk to Mars! So are we condemned to a two-track planet where some countries (or some sections of society within countries) corner material resources and the rest go a-begging? This is the scenario being projected by right wing demagogues worldwide and this is the reason for their recent successes at the ballot box.

Economists and philosophers have tried to redefine human well-being to reflect planetary limits, most notably in recent years by Tim Jackson’s book Prosperity without Growth, which acknowledges that the current definition of economic success is fundamentally flawed. Prosperous societies today increasingly recognize that increased material wealth does not increase well-being. However, most people the world over, regardless of their economic condition, still aspire to some version of the American way of life. This aspiration is reflected in the respect automatically accorded to wealthy people in the world today. A look at the Who’s Who of practically any country includes the names of its wealthiest citizens, together with lists of eminent physicians, lawyers, sportspeople and so on.

Gandhi pithily articulated this state of affairs decades ago when he said: The world has enough for every man’s need but not for every man’s greed. For each according to her needs would be the ideal but, as always, messy reality intervenes. One man’s need is another man’s greed. So it is that millions of well-meaning, virtuous, affluent people the world over would never dream of giving up hard-won creature comforts for the sake of other planetary denizens who are less well off. The spiral of technology has historically been to continuously improve human life, and to continuously create problems at the same time. These problems in turn needed infusions of new technology to solve its problems. So right now, the choices seem to be to outer-planetary colonization, or to invest in defences (gated communities, wealthy enclaves, security guards, border walls) to hold on to material gains. Technology offers a third alternative. The idea of a sharing economy has recently gained a lot of traction. Who needs ownership when mobility and services are seamlessly available? Indeed, ownership becomes a bit of a burden in comparison to the convenience of superb services available on demand with little or no delay.

Even if all this is achieved, humankind’s basic inner restlessness will ensure that we keep wanting more and better, with one eye on the people next door. Global contentment is a moving target. Enter mystic and philosopher Sadhguru and his lectures on inner engineering. His most memorable anecdote in the video (begins at minute 16) is a reminder that all is not lost in the midst of this doom and gloom if we can take the time to laugh at ourselves and the posturings that have brought us to this point.

For more writing by this blogger, see his Amazon page here, or the Google Play Store

Hinkley. Oh no!

The political decision to power ahead with Hinkley Point C nuclear power station is the energy equivalent of appointing a tone deaf musical director to the London Symphony Orchestra. How much more evidence do Cameron and Co. need? A short litany of anti-Hinckley arguments should suffice.

In a case of economics speaking truth to power, the OECD’s 2010 World Energy Outlook quietly increased the average lifetime of a nuclear power plant to 45-55 years, up 5 years from its 2008 edition.

It’s Raining Electrons in Small Spaces

Four recent reports on new breakthroughs in renewable energy generation and storage technology reinforce the promise that was once made for nuclear power: abundant energy for all, including the poorest in society, even though it may never be “too cheap to meter.”

High Performance Flow Batteries The promise of renewable energy technologies will be fully realized when battery storage becomes reliable enough and cheap enough to even out intermittent flows. Today the problem is partly solved by feeding energy from rooftop panels into the grid and then receiving compensation from the energy utility for the power supplied either in cash or in the form of reduced electricity bills. Looking at a typical electricity bill in Euroland (my own) I see the following charges. The unit price (per KWh) is between 6.5 and 7.3 Eurocents, but after grid charges, network costs and taxes are added, I pay 26 cents per KWh. Ironically, bulk consumers (factories, office blocks and large companies) pay lower rates, around 8 to 15 cents per KWh, depending on level of consumption. Now the whole picture is changed with the advent of low cost storage systems that make home batteries affordable and economical. Imagine home systems that can deliver electricity for all your needs at no cost for twenty to thirty years, once installed, barring the onetime cost of the system. Coming soon, to an affordable home near you.

Silicon cones inspired by the architecture of the human eye. The retina of the human eye contains photoreceptors in the form of rods and cones. Rods in the retina are the most sensitive to light, while cones enhance colour sensitivity. Modelling photovoltaic cells based on the makeup of the retina, researchers have been able to enhance the sensitivity of solar cells to different colours in the sunlight that falls on each cell and thereby increase electricity output by “milking the spectrum” closer to its theoretical maximum. Increasing efficiency of the average rooftop PV cells from the current 18-20 to 30% would make such systems cheaper by far than grid electricity mostly anywhere in the world, even in temperate countries. Coming soon, to a rooftop near you.

Modular biobattery plant that turns biowaste into energy. Biogas plants are old hat. They have undeniable benefits, turning plant, animal and human waste into energy (methane) while leaving behind a rich sludge that is excellent fertiliser. However, good designs are not common and they are sometimes cumbersome to feed and maintain. Now comes an efficient German design that promises to be modular and economically viable even at a small scale. In another development, the University of West England at Bristol has developed a toilet that turns human urine into electricity on the fly (pardon the pun) and the prototype is currently undergoing testing, appropriately enough, near the student union bar. Coming soon, to a poo-place or a pee-place near you.

New electrolyte for lithium ion batteries. Lithium ion batteries using various electrolytes have already become the workhorse of the current crop of electric cars and for medium-sized storage requirements. New electrolyte chemistry discovered at PNNL Labs shows that reductions of upto ten times in size, cost and density are feasible and various electrolyte/electrode combinations are being further tested for production feasibility. Coming soon, to a battery storage terminal near you.

So what should you do, as a concerned global citizen, until you can lay your hands on one of these devices (or all of them) for your own use? Tread lightly on the earth, don’t buy bottled water, reduce energy use, walk when you can instead of driving your car (your arteries will love you for it), buy local produce, eat less meat (your grateful arteries again), think twice before flying off to that conference (think teleconferencing), buy an electric car if you need a new one, and remember that every liter or gallon of petrol you fill into your old one not only fuels your car but potentially also the conflicts in the Middle East and/or lines the deep pockets of Big Oil which definitely does not want your energy independence.

The Flea on the Behind of an Elephant

Scroll backwards in time to the early 1970s. US President Richard Nixon appointed the Atomic Energy Commission (AEC) to produce a study of recommendations on “The Nation’s Energy Future” based on advice from the National Science Foundation (NSF). Requesting the AEC for energy prognoses is akin to asking a tiger for dietary recommendations; there will surely be no vegetables on the menu! Dr. Dixy Lee Ray, chair of the AEC, predicted in her summation of the report that “solar would always remain like the flea on the behind of an elephant.” In the early 1980s I knew another eminent researcher, Dr. Thomas Henry Lee, a Vice President for research under Jack Welch at General Electric, who often stated that nuclear power would produce “energy that is too cheap to meter,” essentially free.

The AEC study, when it was published, proposed a $10 billion budget for research and development with half going to nuclear and fusion, while the rest would be spent on coal and oil. A mere $36 million was to be allocated to photovoltaics (PV). Dr. Barry Commoner, an early initiator of the environmental movement, was intrigued that the NSF had recommended such a paltry amount for solar. In the 1950s he had successfully lobbied for citizen access to the classified results of atmospheric nuclear tests and was able to prove that such tests led to radioactive buildup in humans. This led to the introduction of the nuclear test ban treaty of 1963.

Dr. Commoner’s own slogan (the first law of ecology is that everything is related to everything else) prompted him to question the AEC’s paltry allocation for solar PV, especially since he knew some of the members of the NSF panel who advised on the recommendations. He discovered the NSF panel’s findings were printed in a report called “Subpanel IX: Solar and other energy sources.” This report was nowhere to be found among the AEC’s documents until a single faded photocopy was unexpectedly discovered in the reading room of the AEC’s own library. The NSF’s experts had foreseen in 1971 a great future for solar electricity, predicting PV would supply more than 7% of the US electrical generation capacity by the year 2000 and the expenditure for realising the solar option would be 16 times less than the nuclear choice.

Clearly, the prediction of 7% solar electric generation has not yet happened, but current efficiency improvements in photovoltaics and battery storage technologies point the way to an energy future far beyond what the NSF predicted in 1971. Fifty years from now, it is nuclear power that is likely to be the flea on the behind of a solar elephant.

Molybdomancy

I started off intending to write about the Austrian New Year’s Eve custom of Bleigiessen and learnt several things today. First, the posh name for the practice is molybdomancy: the art of divining the future from the shapes of molten metal that is quickly thrown into cold water. Second, this is not only an Austrian custom, but is widely practiced in Germany and in the Nordic countries as well. Apparently in Finland, the practice goes by the name of uudenvuodentina and is quite popular. According to this source, the practice originated in ancient Greece and later travelled to the Nordic and Central European countries where the custom is still followed today, although the results are interpreted more in a spirit of fun rather than being taken seriously. No wonder the word molybdomancy has been quite forgotten!

Originally made from tin, nowadays bleigiessen sets are sold in the streets in the week preceding New Year in small bags consisting of half a dozen pieces of tin or lead alloy mixed with cheaper metal. The pieces are molded into shapes associated with good luck; horseshoes, pigs, chimneysweeps, toadstools or 4-leaf clovers. I bought a bag for New Year’s Eve and settled down with six of my nearest and dearest to see what 2015 has in store for us.

As you can see, the results are outstanding! 2015 is going to be a wonderful year for the family; two of them will perform exceptional deeds, while the rest will be merely brilliant. I wish all my readers a similarly uplifting prognosis.

Love Oil, Hate Oil

The story of oil begins more than 2,500 years ago. Reliable indicators show that in China people were drilling a mile deep with bamboo pipes to recover natural gas and liquid hydrocarbons that were used as a source of fuel for fires. This was before the start of the Han dynasty in 400 BC. See this fascinating slide presentation on the progress of drilling technology by Allen Castleman, a self-confessed oil redneck.

The modern oil age is popularly considered to have started in the 19th century with the use of internal combustion engines for everything from pumping water to transportation. A glorious age, but now it’s time to move on (pun intended) to other fuels. As Saudi oil minister Sheikh Zaki Yamani predicted more than three decades ago, “the Stone Age did not end for lack of stones, and the Oil Age will end long before the world runs out of oil;” a statement at once prescient, rueful and flippant. In today’s lugubrious world, they don’t make oil ministers like that any more.

As a reminder that the world turns and turns and comes full circle in more ways than one, here’s a parting thought; an article from the Guardian of 30 January 2014. In 2013 alone, China installed more solar power than the entire installed capacity in the US, the country where the technology was invented. There is a caveat to the article that some of this newly installed capacity is not yet connected to the grid but, once installed, connections are only a matter of time.